Introduction

The artist’s journey is never a straight path, there are countless twists and turns. Shane and I begin a new dialogue about the life of the artist and the creative process. There is always so much to ask Shane about his studio process and how he continues to be inspired to make work. We thought to share this new discussion and a series of paintings that initially began in 1989 as charcoal drawings called the “Numbers” series. Last year, Shane revisited this body of work and then started making oil paintings. This series in oil is now referred to as “The Counting of Days”, it’s an intriguing body of work based on humanity and life itself.

“The Life of the Artist and the Creative Process”

A Conversation between the studio manager (Victoria Chapman) and Shane Guffogg.

I would like to begin by sharing some text Hegel wrote in the Phenomenology of Spirit, (1807). This book was written to inspire philosophical stimulation. I found the chapter on consciousness: “Sense-Certainty: or the ‘This’ and ‘Meaning’ quite fascinating. It discusses that to be creative, one needs to have a sense of consciousness; to focus on the here and now before commenting or even interpreting on surroundings. You have created many paintings that lead into this idea, one such, 2015, “What if Everything That was Is, And Everything That Is Never Was.” From my research, it seems Cezanne spent a great deal of his life by himself, being in nature painting Mount Victorie. But first, the great artist needed to understand his existence experiencing the here and now.

What do you have to say about consciousness and the here and now?

Shane Guffogg: You are coming out of your corner with a big, left hook type of question! The title of the painting that you quote is an interesting story. As I was working on that painting, trying to create subtle transitions of hues that were almost invisible but giving enough information to show the viewer what is there, the title popped into my mind, seemingly from nowhere. I wasn’t thinking about what the title should be or what the painting was saying, but it was the subtle tones that influenced my mind to summon that idea; an idea that all that has ever been, is present in each moment, and the moment, or as I like to call it, the now, is just that. It has no past or future. It is a seemingly impossible thing to comprehend as this idea of everything being nothing and nothing being everything counters each other. But, when I can just be in the moment, then it makes perfect sense.

As for Cezanne and his need to be alone, I think it is true for some artists, but I can’t say for all. Creating is very personal and in my case requires quiet, uninterrupted space, just like when we have our quiet thoughts. They need to be private. There is an innate silence in my work that I think comes from creating in solitude.

Shane Guffogg, “What If Everything That Was Is, And Everything That Is, Never Was” oil on canvas, 48 x 60″, 2015

Another work you began in 1989 in charcoal on paper and recently returned to in pastel for the 2020 exhibition, “The Path of Light” at Casa Regis: Center for Culture and Contemporary Art, Italy, was the “Counting of Days.” This came about because you were creating site specific work for the 17th century building, former monastery, and the exhibition was to be opened on December 24 during the Winter Equinox.

Tell me about the progress of the “Counting of Days” series from 1998 to the present and how you moved from works on paper to oil on canvas to further develop this visual language.

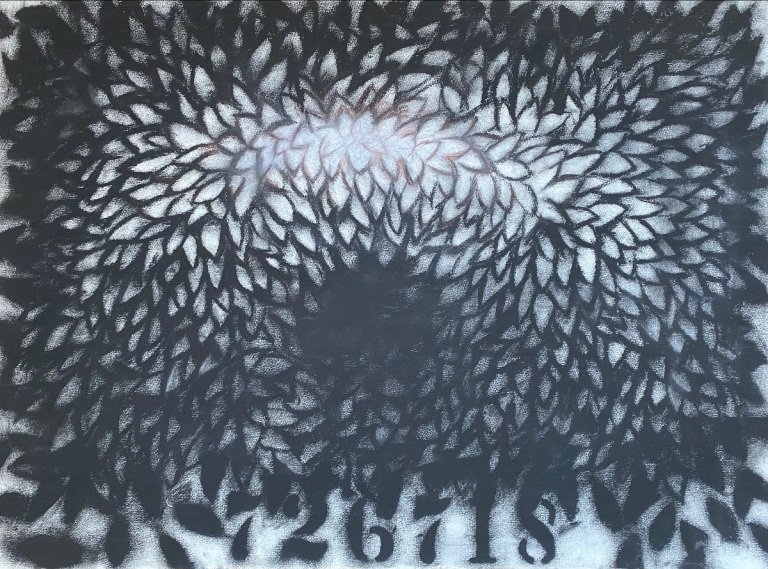

Shane Guffogg: The numbers at the bottom first appeared when I returned from a trip to the former Soviet Union in 1989. The Soviet regime was nearing its end as I traveled across Ukraine on a Peace walk with 70 other Americans, meeting people and seeing their views of life and history. I realized, firsthand, that the winners of war write the history books, be it right or wrong. But I also began to think about how we keep track of time in a different way other than counting years. I think this came about because each day of this Peace walk was like a year in terms of the experiences I was having. The western world uses a yearly count called the Gregorian Calendar, which is, as some may know, a solar dating system that was proclaimed in 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a reform of the Julian calendar. Why this matters is because I was thinking about time as history. And beyond that, how we count time and make it history. So, I started wondering how many days had transpired from the beginning of the Gregorian calendar, assuming there is a day one. I did the math and added the leap years and realized how many days had transpired on the day I finished the charcoal or pastel drawings. But the shapes in the drawings were an extension from the Memory series of paintings and drawings I had been working on from 1985 to 1988. And to digress for a brief moment, the memory series were spawned by my moving to NYC and then traveling to the Greek island of Paros. What this journey brought about for me was an acute realization of where I was from and the memories I had accumulated and stored away. How the brain stores memories is a phenomenal thing. What I began to realize was that as more memories are added, they become compressed and merge with other memories, created new memories that are fragments all put together like a mosaic. I bring this up because the shapes of leaves or flowers, etc. are not actual images of leaves or flowers. They are informed by memories of these objects.

Shane Guffogg, “726718”, charcoal on paper, 22 x 30 inches, 1989

Detail of “Counting of Days”, oil on canvas

Recently a friend shared the essay, “Against Interpretation” by Susan Sontag, (1966), studying this text allowed me to return to the foundation of the art-making process. Acknowledging once an artwork is complete, the viewer shouldn’t need to review symbolic reference material to interpret it. My hope is that the artist has inherent accountability in a conscious state of mind, creating a link, rooted in the here and now – that there is a reason for its existence.

I understand this is a huge topic, but what are your feelings about the life of the artist and the conscious effort to understand the artwork? For example, once the artwork is finished what tools are you willing to give the viewer for interpretation? Should this be a genuine effort made by the viewer only based on what they see and feel in front of them? Or does the artist need to create art with symbolic references to explain the narrative? And how does this apply to abstract art?

In Sontag’s essay “Against Interpretation”, she writes: “In most modern instances, interpretation amounts to the philistine refusal to leave the work of art alone. Real art has the capacity to make us nervous. By reducing the work of art to its content and then interpreting that, one tames the work of art. Interpretation makes art manageable, comfortable.”

Shane Guffogg: That is a very tricky set of questions. A museum can put up all kinds of placards and produce great audio tours using the voices of famous actors to enhance and educate the experience. This doesn’t mean the audience will engage in this and may prefer, as I do, just to walk through and take it in on my own terms! Art is a subjective thing, and the original intent of the artists may not be received by the viewers. But on the other hand, if the artist is truthful with themselves, that intent of truthful expression can transcend and reach an audience in ways the artists may never have intended or even thought of.

I do think of artists’ statements as a kind of handle for a suitcase. The written word by the artist makes the suitcase easier to carry, if I can use that metaphor. I also feel that it is important for artists to write about their work as a way of understanding why they are making it. Art is a form of communication, so what is it that is being communicated. Granted, sometimes art goes beyond language, and it requires our presence to fully grasp the intent of the artist. And when that happens, it really is a profound moment. I was recently in Italy and spent time looking at and studying the masterpiece by Caravaggio, The Seven Acts of Mercy.

Seeing it in books or online is one thing, but standing in front of it creates an entirely new experience since the painting is over 12 feet tall. This painting is a great example of the artist’s intent versus what is written about it. I read about the painting and watched a documentary on it, but that didn’t tell me what I needed to know. What I wanted was Caravaggio’s views of life, not an art historians’ take. By standing in front of the painting, I began to recognize and understand his views of life more, which then gave me a deeper appreciation for the work.

A painting from Shane Guffogg’s “Memory” series:

“Mirror”, acrylic on canvas, 45.25 x 45.75 inches, 1986

You recently wrote this about “The Counting of Days”:

“A painting that is about the randomness of order and the fleeting moments that are real but fragile, with some being transparent. These shapes aren’t leaves or petals of a flower, but the natural movement of my hand when I randomly make a shape. And once repeated, it turns a subconscious moment of mark making into an image that is informed by the events of my life.”

This is so beautifully written touching on all the accounts — here, now, descriptions, your hand movement — how this has developed through your own psyche or even subconscious moment.

Shane Guffogg: I feel that when my conscious and subconscious mind are communicating via the piece I am working on is when they are most successful. Now, of course, these are just words and I have no actual proof that this activity is happening, but I have no way of proving that it is not. This brings us full circle to the title of the first painting you quoted, “What if Everything That was Is, And Everything That Is Never Was.” That is where we are, maybe where we always are?!!

One last thing about “The Counting of Days”, the latest painting I just finished, has the number of days I have been alive on this planet instead of the year count of the Gregorian calendar. A different count but one that is more relevant to me in the here and now.

Stay tuned as the conversation continues.

On the easel – a close up of the numbers on the “Counting of Days”