We continue with Frida Kahlo and Francis Bacon

Shane Guffogg, "One Second Before Midnight" (self-portrait) 2020

Oil on canvas, 10 x 8 in.

(conversation between Victoria Chapman and Shane Guffogg continues)

Previously we discussed the work of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. In Part 4, we dive into self-portraits by Frida Kahlo and Francis Bacon. This is an important discovery in the history of portraiture. Guffogg and I weave in and out of each artist's life, understanding how they arrived.

VC: Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) was an artist who had incredible merit. By following her impulses she transcended her own life. She is well-known for her self-portraits, of which she painted around sixty. These portraits helped her find freedom and escape herself. As a child, Kahlo contracted polio. At age 19 she was in a traffic accident that left her with a broken spine, pelvis, and collarbone, as well as a crushed foot. This grueling event would change the course of her life; her plans to become a doctor were shattered. She was permanently crippled and at times bedridden for months on end. Throughout her recovery, she found painting to be her saving grace. Eventually, she placed mirrors around her room, delicately painting herself to pass the time and the onslaught of endless pain. Kahlo went on to develop her artwork in this manner. When her health improved she sought out muralist Diego Rivera to see her work. He simultaneously recognized her talent and fell in love with her. Kahlo and Rivera would eventually marry. They began traveling around together for Rivera’s many mural commissions, visiting San Francisco, Detroit, and New York, before returning back to Mexico. Kahlo would continue to create paintings describing her life, which included countless surgeries, questions about identity, and the endless suffering of Rivera’s infidelity. These topics were reoccurring themes found in her compositions. The painting “The Two Fridas” (1939) displays two images of Kahlo. She made this painting after a separation from Rivera; the two Fridas represented the Kahlo that Rivera loved and the one that he rejected. Kahlo would often wear traditional Mexican or Tehuana clothes, adorned with fresh flowers in her hair and abundant jewelry on her fingers and wrists – this was the feminine Frida Rivera adored. But when Kahlo suffered from Rivera’s infidelity, she would often cut her hair short and dress in men's clothing – this was the Frida Rivera did not like. In her painting, there are two Fridas holding hands and showing their hearts, one donning ornate attire and the other dressed more casually. Their hearts are connected by a vein, however, the ornately dressed Frida is cutting a secondary vein off of her own heart.

Frida Kahlo, "The Two Frida's" 1939

Oil paint, 68 x 68 in.

V.C: This investigation of self often dominates Kahlo’s paintings. Kahlo endured a massive amount of physical hardship; she had multiple miscarriages and natural abortions. These experiences were terribly difficult for her, as she desperately wanted children – she often painted herself with small monkeys, symbolically showing her desire for fertility. Near the end of her life, Kahlo had to have her lower right leg amputated due to gangrene. Trying to make light of this, she wrote in her diary, “Pies para que los quiero, si tengo alas pá volar” [Feet, why do I want them if I have wings to fly]? In an early painting, titled “My Birth” (1932), she depicted a woman birthing her, with her head reaching all the way out of the vagina; but the painting also serves as a dark reminder of death, as the person giving birth is wrapped tightly in a sheet that spans from her head to her ribcage, in an empty room ungracefully laden upon a bed. Frida, herself, looks like she might even be a stillbirth, as the sheets beneath her head are bloodied. On the wall above the bed is a religious painting of a woman wearing a crown of thorns. The religious portrait was said to be typical of the type of paintings Kahlo’s mother liked. After doing some research on this, I found that Kahlo created this painting after a miscarriage.

Frida Kahlo, "Self-Portrait with Monkey" 1938

Oil on masonite, 16 x 12 in.

V.C: Unsurprisingly, Kahlo is considered an international icon. I think this is partly because her work shares intimacy and connects with the viewer – drawing them into her narratives – but also about the evolution of her life and the transition of her healing process. In each portrait, the artist exists neutrally despite her pain, not simply focusing on the negative feelings that it can bring about. Each self-portrait is a journey of investigation and discovery. The painting “Roots” (1943) seems to be about belonging in the spiritual world. Her painting “The Wounded Deer” (1946) symbolizes trauma, and “The Broken Column” (1944) shouts equally of agony and courage.

Andre Breton, who wrote the Surrealist Manifestos, labeled Frida Kahlo a surrealist, however, she vehemently denied that: she was painting her truth. A lot of your self-portraits seem to draw from the surreal; are you painting your imagination or your reality?

Frida Kahlo, "The Broken Collum" 1944

Oil on masonite, 16 x 12 in.

Shane Guffogg: That is a really interesting question. The short answer is both. The extended version is that my reality and imagination are 2 sides of the same coin. Once my imagination is fully embraced it becomes my reality. I think of imagination as a form of daydreaming, where the mind goes on a walkabout, picking up shapes, colors, objects, etc. Then my mind arranges these moments, making them into a new moment that is a hybrid of my imagination and reality. A perfect example is a painting like "The Verdict and Prophecy of Spring." Spring begins on March 20th and Mueller's verdict on whether or not Trump knowingly colluded with the Russians was announced on March 22nd. This painting has what looks like the fabric of the robe of an English judge, with a down-turned mouth showing his disdain for what is being said. From that grows a nose that is the color of an Italian squash, which I had just planted in my garden. There is my eye, peering out from the position of the third eye, or inner eye, at the top of the squashed nose. To the right is a nondescript profile, maybe it is mine – I wasn't basing it on anyone and it was done from memory. There are 2 other eyes that are blue, which mine are not, but the majority of all the US President's are. On the right we see the rays of the sun shining, ushering in spring. The painting is like a snapshot of a moment of my life, but the individual parts have been morphed together like a dream.

Shane Guffogg, "The Verdict and Prophecy of Spring" 2019

Oil on canvas board, 12 x 9 in.

VC: It’s important to remember when looking at Kahlo’s work that she was born just before the Mexican Revolution. By 1920, Mexico –particularly Mexico City – had a cultural renaissance. There was a mission to rebuild Mexico after so many years of conquest. Rivera had returned from Paris, where he was studying cubism and was hired alongside other artists to paint murals around the city to help educate and empower the people by depicting their heritage, creating new solidarity. Rivera took pride in painting these murals. Within this atmosphere, Kahlo became a woman who explored free thought and new associations on how to live, speak, and document the world around her. Kahlo was a visionary and her paintings were without boundaries.

Andre Breton described her as “A ribbon with a bomb around it,” for she was incredibly creative and a great seductress. In 1927, Rivera and Kahlo joined the Mexican Communist Movement and arranged to have the Russian Revolutionary Leon Trotsky and his wife stay in their home in Mexico City, which lasted a few years. Kahlo had an affair with Trotsky and created a self-portrait for him as a lasting gift, but when he left their house, he did not take it with him.

Kahlo lived an incredible life, leaving her self-portraits as a testimony to her profound artistry. She said she did not set out to be a painter, rather she painted for herself as an escape from her suffering. Some of these paintings are haunting and hard to look at. She thought of them as a type of ‘ex-voto’ (an image that would encourage miracles or a religious vow). What did you think when you saw your first Frida Kahlo painting? Where was it and which one was it? What did it teach you?

Frida Kahlo, "Diego on my Mind" (Self-Portrait as Tehuana) 1943

Oil on masonite, 29 9/10 x 24 in.

Shane Guffogg, "Red Face, Blue Hand Self-Portrait" 2018

Oil on canvas board, 12 x 9 in.

Shane Guffogg: She did have a painful life that she documented through her art. Again, she became a shaman and took emotional and spiritual journeys, and brought back her findings which she shared through her art. Her work is so steeped in her own personal visual language, but yet it is also universal. I saw a retrospective of her work in New York 20 plus years ago. What I found so interesting is how she literally shrugged off what was considered important or progressive art at that time. She had her own agenda, which was to see herself and bare witness to her own emotions and physical pain. The exhibition was small but left a lasting impression. There were a lot of people, all trying to get as close as possible to the paintings, which made it very hard to see the work and spend the necessary time to absorb them.

VC: I was listening to a lecture on Frida Kahlo by New York based art historian, curator, and critic Hayden Herrera (who also wrote a biography on the artist which then became the film “Frida”), who spoke about the 2009 exhibition, “Frida Kahlo: Her Art and Life” which traveled through Boston, San Diego, Austin, and onward to Berlin and Vienna. The lecture had some very interesting things to say about Kahlo’s artwork. After the lecture a guest had a defining question, which was the fact that Kahlo was a self-taught artist and a very good one. But the artist also painted some very realistic portraits that were also very well painted, but when she came to make her famous self-portraits she chose to paint in a more primitive manner rejecting a realist style. The curator thought Kahlo made this choice, because the viewer would better transport themselves into her applied narrative through a primitive technique rather than super realism. What do you think about this revelation? As I noticed you have done the same.

Shane Guffogg: I know what it means to be self-taught – I never did have a painting lesson or class. Actually, I avoided them for fear it would send me in the wrong direction creatively. Paint has multiple personalities – it can be refined, leaving no trace of the maker, or it can be crude with thick gobs of paint that speak of a primordial emotion. Her choice to paint them in more of a primitive manner adds to the emotional fervor of her imagery. Her images are like pictographs from an Egyptian tomb; stylized and direct. They bypass our need to wonder how they were made and instead stand as a testament to her experiences in life.

Shane Guffogg, "Self-Portrait" 1988

Oil, charcoal, and ink on paper, 42 x 42 in.

V.C: Another artist that sought out to investigate the human condition was Irish-born, Francis Bacon (1909-1992). Bacon made many self-portraits throughout his career. Interestingly, they share key components, which are a combination of abstract contorted figures set amongst stark backgrounds, with structural line and symbolic shapes revealing an evolving narrative. The portraits include a practice of what Bacon called ‘injury’ where he amplified facts about his subject displaying a truth. Bacon concluded by saying he chose to arrive at this path tapping into primitive space byways of an accident. A trial and error of sorts. If he didn’t succeed in fulfilling this on canvas, he destroyed the painting, leaving no trace. Today we only see half of what the artist painted, because he never painted over a work.

What are your thoughts about painting over an artwork as opposed to starting a new canvas? Is there underlying energy that lingers from the past composition that is haunting? Or is it merely technical based on the necessary material one uses?

Francis Bacon "Self-Portrait" 1956

Oil on canvas, 78 x 54 in.

Shane Guffogg, "Self-Portrait with Male Torso" 1983

Oil on canvas, 60 x 48 in.

Shane Guffogg: Francis Bacon’s work was about spontaneity. The brush strokes were about, in my opinion, the moment between life and death. He would take a primed canvas and stretch it on his canvas bars reverse so that he was painting on the raw side of the canvas because the canvas had a different tooth and it would catch the paint differently than the primed side. Because of this it was impossible for him to go back into the painting and rework it. So the spontaneous moment of his brushstroke was so much about chance and the moment that he was in. It’s very easy to lose a painting. It’s happened to me many times over the years. But because I paint on the gessoed side, I can rework the paint.

Bacon made many self-portraits throughout his career, I found little reference about them. In an interview, between art historian John Richardson and painter Lucien Freud, who were both friends with Francis Bacon, they recall seeing Bacon applying Max Factor makeup to his face. Bacon was literally ‘rehearsing’ how he would apply paint to canvas. They both remarked about how Bacon’s make-up application would inform him about the gesture he would need to make to lay down the paint. The out-come of Bacon’s self-portraits, feel less of an ‘injury’ or tampering of his image as opposed to the fracturing he would do to other portraits of friends and lovers.

Do you do any special studying of your facial features to create any portraits?

Shane Guffogg, "Self-Portrait 4/7/1983"

Pencil and acrylic on paper, 14 x 11 in.

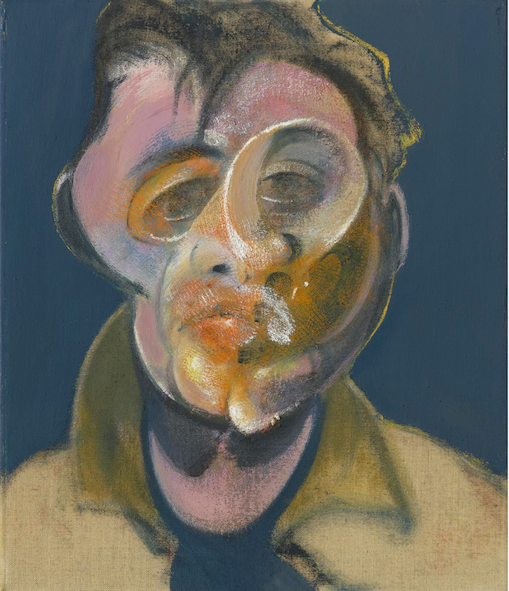

Francis Bacon, "Self-Portrait" 1969

Oil on canvas, 14 x 12 in.

Shane Guffogg: That is so interesting that he rehearsed by applying make-up. He was a bit of an over-the-top drag Queen without the drag, so it makes sense that he would use makeup to explore his face and the structure and how light falls on the bones as a way of learning how to paint. When you look at his paintings, or more specifically his portraits, the paint is applied in that way as if he's applying makeup in a morgue on a dead body.

Bacon’s art career began after seeing Picasso’s crucifixion paintings, whereby he set out to create his own. These paintings were not related to religion but were about Bacon’s feelings and well-being. The artist said he considered these to be a portrait of sorts relating to human behavior. He said this in an interview with art critic David Sylvester, “Francis Bacon Fragments of a Portrait” (1966) “The crucifixion is the armature of expressing these opinions.” The artist took inspiration from photos of animals in slaughterhouses just before they were killed. Bacon was inspired by Rembrandt and one can see the influence a painting like “Slaughtered Ox” (1655) had. In the interview, the artist talks about Rembrandt's self-portrait “Autoportrait Aix” (1659) and how the old master’s handling of the eye sockets appeared to be abstract and ahead of its time. Bacon went on to say there is a sense of embodiment and through the brushstrokes, he knew more about Rembrandt the painter than Rembrandt the auto-portrait.

What are your thoughts about reading through the artist’s brushstrokes to understand something more?

Shane Guffogg "Self-Portrait Age 20" 1983

Ink on paper, 14 x 11 in.

Francis Bacon "Three Studies for Figures at the base of the Crucifixion" 1944

Oil and pastel on Sundeala fiberboard, 37 x 29 in. ea

Francis Bacon, "Three Studies for a Crucifixion" 1962

Oil on canvas, triptych, large scale

Shane Guffogg, "The Wait" 1983

Mixed media on paper, 8 3/4 x 5 1/2 in.

Shane Guffogg, "The Wait" 1983

Mixed media on paper, 8 3/4 x 5 1/2 in.

Shane Guffogg: I agree with Francis Bacon about learning more about Rembrandt through his art or through his brushstrokes than by reading about him. And the same is true for Francis Bacon. We know through his paint handling he had a tendency for violence and was fascinated by the survival of the fittest in the animal world. Photography played a big part in his work, especially with the Muybridge photographs. Oftentimes, when we look at an image, we put our own thoughts onto it but seeing multiple photographs of say 2 male wrestlers who are intertwined gives us a different idea about an actual moment. That’s what he was after, that moment that can only be described through paint.

V.C: Valesquez’, “Portrait of Innocent X” (1650) was another painting Bacon was influenced by and he went on to create his own interpretation. When Bacon was in Rome he chose not to see the famous portrait, he preferred to work from photographs. Bacon said in the same interview with David Sylvester, working from photographs was a much better option, as he would not be inhibited by the original or the sitter he was painting. Eventually, he had his friend John Deacon photograph his models and used Eadweard Muybridge stop motion images to understand the figure. Towards the end of his career, Bacon’s artwork became softer and less violent. It’s fascinating to look at his entire body of work and see the transitioning states.

Your works come from a completely different place, but the texture found in Bacon’s paintings is said to be incredibly interesting, as he used dirt and all kinds of small particles found on the floor of his London studio. What are your thoughts about his artwork? Did his paintings influence your portraits in any way? I imagine Bacon’s contorted portraits may have had an impact on your thought process, even if they came from a completely different place.

Francis Bacon, "Self-Portrait" 1975

Shane Guffogg: When I first discovered Bacon I was floored. I was in my late teens and I checked out every book the library had on him and read them cover to cover. One essay I read about him posed a question, which was if aliens from another planet came to earth and judged humans by the art they made, what would they think of us based on Francis Bacon's work? His quick brushstrokes create the sensation of flesh deteriorating, which is a very existential, angst-ridden subject to be swimming in. I was very influenced by his work in my early years because he made me look at the human form in a new way. That coupled with normal teenage anxiety made Bacon hit the mark. Self-portrait Age 20 is a good example. In this drawing, I took the square and circular motions from Bacon as a way of defining a space around my body. My shoulder is the only part of me that is in the drawn cube; the rest of me is entangled in the swirls, which are seemingly withering my body away to skin and bones. Another example is Standing Before the Mirror from 1983. In this painting, my back is painted as if I have the back of a muscle-bound human gorilla, but my reflection shows another side of me – a female whose body has been warped and disfigured. The flesh is almost melting off, revealing the contorted ribs, which I took from the right panel of Bacon's Three Studies For Figures At The Base Of A Crucifixion. The images are a portrayal of human suffering, pain, and anxiety. He often tied religion into his imagery, like his screaming popes. But my reflected image was also being informed by Grunewald's crucifixion painting, which I am sure Bacon was also looking at. The imagery of my two panels doesn't match up and that was on purpose. It is meant to visually add to the disjointed moment of alienation between the mind and body.

Shane Guffogg, "Standing Before the Mirror" 1983

Oil on canvas, 72 x 40 in.

Francis Bacon, "Three Studies for Self-Portrait" 1979

Shane Guffogg, "Grey Mask Self-Portrait" 2018

Oil on canvas board, 14 x 11 in.

V.C: Bacon’s personal life was quite complicated; he had a love-hate relationship with his father who was a racehorse trainer. During the artist’s adolescent years he would sneak off to the stable for sex with men, later his father would find out sending stable boys to whip him. Art historian and Bacon’s friend, John Richardson, wondered if the artist’s early beatings from his father gave him a taste for masochism. This type of affection through violence would later be played out by Bacon’s lover, Peter Lacy. Once, Richardson recalls, while in a drunken state, Lacy hurled Bacon through a plate glass window. Bacon and Lacy’s relationship was often fueled by violence and sexual displays that the artist would refer to as a place of satisfaction. Bacon believed this darker side, where one is placed in the terrors of existence, was a part of humanity and he wanted to paint it. Many of Bacon’s paintings are derived from his relationships with his lovers. Some of this violence may have been second nature, as Bacon grew up during two world wars and during the Second World War, he volunteered in the Civil Defense Service in Air Raid Precaution. This was during the London Blitz, seeing this devastation during the horrors of war must have been impactful on some level.

In 1971, George Dyer, who was Bacon’s lover at the time, after a night of drugs and paid sex, died on the seat of a toilet in their hotel room. Bacon ended up staying in another room that night. This was the evening before the opening of Bacon’s exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris. The death was rumored to have been a suicide. Bacon had created many paintings of Dyer, who was from London’s underworld and brought much diversity to their relationship. After the exhibition was over, Bacon went back to London to paint another portrait of Dyer, but he couldn’t get anything out. Consequently, Bacon returned to Paris to stay in the same hotel where his lover died. Bacon hoped to finalize his emotions, and paint them out onto the canvas.

Bacon’s interviews are very interesting, at one point he considered himself a realist painter, because even though the imagery that came out was abstract. Bacon said the emotions he brought about to the viewer came from real-life emotions. I had never thought of realism in this way before.

You also consider yourself a realist painter and your “Sapere Aude” series, is derived from the physical body and being but the composition is seen as abstract. Can you explain more, and does this flow over to some of your portraits?

Shane Guffogg "Untitled Mask 2019-5"

Oil on canvas board, 8 x 10 in.

Shane Guffogg "Sapere Aude #5" 2017

Oil on canvas, 84 x 60 in.

Shane Guffogg: I think of abstraction as a subject matter in a similar way that maybe, an artist may paint a still life, with the flowers becoming the subject matter. But I paint my abstraction as a real subject, and by that I mean it has an actual space that it occupies as one line goes over another creating a shadow. Francis Bacon’s portraits were indeed a realistic view of the human psyche. And I do believe growing up in World War Two in the violence that he was surrounded with and the fact that his father did not accept him played a huge part and his need to paint humans almost as animals. The figures are in a moment of decay becoming grotesque at times. Again the fact that he painted the screaming Pope paintings that were derived from Velazquez, speaks more about almost a disdain for authority, especially in the context of religion.

Francis Bacon's, "Three Studies for a Portrait of George Dyer" (in 3 parts); oil on canvas, Size: 14 x 11.8 in. Sotheby's London: Monday, June 30, 2014, sold for $45 Million (www.artnet.com)

V.C: Another point was, he was inspired by Egyptian art, especially those dating as early as 2600 B.C., as he felt Egyptian art was an attempt to defeat death. Also, he took inspiration from early Greek art and literature. One example was the Furies because it was ‘haunted by guilt.’ One passage he recited was, “The reek of human blood smiles out at me.” Bacon said text such as this, brought about a magnitude to translate into the visual. Has any of your self-portraits been inspired by ancient art or early text? I remember you saying you have read from the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Shane Guffogg: Ancient art has always inspired me. The Sumerian winged gods are a great question for me. They represent an ideology that we don’t quite yet understand. The Egyptian sculptures were about perfection. When you look at some of the faces of the Pharaohs that were carved in stone, they're not actual portraits of a person. The left side and right side of the face is perfectly mirrored and symmetrical which doesn't occur in nature. So those portraits again we're giving us their ideology. Now when we look at Francis Bacons' portraits, we see the effects of World War One and World War Two and the horrors that were etched into the human psyche.

Shane Guffogg, "Untitled - Mask 2019-2"

Oil on canvas board, 14 x 11 in.

Stay tuned for more conversations

Victoria Chapman

Studio Manager

A very special thanks to Neville Guffogg for editing.

Note: all images shown in this email are (fair use) public domain