The dialogue continues as we explore the inspiration behind this magnificent poem – Victoria Chapman

February was a busy month for Los Angeles – there were many art fairs that took place among the forever sprawling and busy city. I went to most of these fairs hoping I might see something new, something that would give me insight about the world and remind me why being alive is so important. Isn’t art suppose to improve on what already exists? Or as Picasso was once quoted: “Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life”. In these times of global change and the ongoing slew of Trump era politics, I was searching for art to give me something more. Nothing I saw moved me. Instead, I saw art that was dull with no narrative or content. It was hollow, fractured, dry and brittle, bearing no shelf life. It was even poorly made. Haphazard and pretentious are other words I would use to describe what I saw. I did not feel a pull of energy drawing me in or a gleaming light of ecstasy that would make me feel connected to another source. What I saw was mostly vapid works that were unloved by the maker. Why did these works matter? For some, the laugh was on the viewer. It made me wonder what kind of society we live in? If this is a statement unto itself — bad art is being made by bad artists because politically and economically we have fallen and are now spiritually bankrupt — then what? I had to ask myself again, why hasn’t anyone stepped up to the plate and made a painting that changes history the way Picasso did with Guernica in 1937. The painting was a reaction to global change that would set nations on to a path leading to World War II. All this got me thinking, where are those artists who were ushered in as the “shamans” of our society, whose purpose is to find and pass along the deeper meaning on life? I believe artists are born and not formed in schools like machines. They have an inherent DNA, able to receive layers of telepathic visions and sounds, retrieving this information to share with our society through their creative process. Artists and writers are extraordinary people, filling in the “amnesia” of the past to restore us to now. I think about Rilke’s advice to a young poet, where he exclaims, to be a good writer – it is to be found inside, to listen deeply to oneself and create work that is meaningful and honest.

Paris

February 17, 1903

Dear Sir,

Your letter arrived just a few days ago. I want to thank you for the great confidence you have placed in me. That is all I can do. I cannot discuss your verses; for any attempt at criticism would be foreign to me. Nothing touches a work of art so little as words of criticism: they always result in more or less fortunate misunderstandings. Things aren't all so tangible and sayable as people would usually have us believe; most experiences are unsayable, they happen in a space that no word has ever entered, and more unsayable than all other things are works of art, those mysterious existences, whose life endures beside our small, transitory life.

Rainer Maria Rilke - Letters to a Young Poet [The First Letter, paragraph one]

Letter To A Young Poet

Rainer Maria Rilke, (4 December 1875 - 29 December 1926), was a Bohemian-Austrian poet and novelist. He is "widely recognized as one of the most lyrically intense German-language poets". He wrote both verse and highly lyrical prose.

In 1902, a 19-year-old aspiring poet named Franz Kappus sent a letter and some of his work to the poet, Rainer Maria Rilke, and politely asked for some feedback. Some months later, the following invaluable response reached Kappus, and it didn't end there — over the course of the next 5 years, Rilke continued to write to him with advice. In 1929, three years after his idol's death, Franz Kappus published Rilke's ten letters in a book.

Rilke’s letter is an important reminder to look within. Taking moments to reflect. As I continue with T.S. Eliot’s long poem, “Four Quartets”, I am reading Burnt Norton, Section II, highlighting each line Guffogg has titled a painting from. I think about what the writer was experiencing during World War II, wondering what the world was like, or what it was to become, and ask, what of that world continues today? This all ties into my observations of Guffogg in his studios creating his visual diary based on Eliot’s poem. Reviewing lines 49 – 53, I start to make notes from one of the many guides I found online. Details, for example, when Eliot uses the word, ‘mud’ it is eluding to war and the battlefield. A reminder that Eliot wrote this section before the outcome of World War II and wrote the rest when the Germans were bombing England.

Thomas Stearns Eliot, (26 September 1888 – 4 January 1965), was known as one of the twentieth century's major poets, also an essayist, publisher, playwright, and literary critic. Eliot was born in St. Louis Missouri in 1888 and later moved to England in 1924 at the age of 25. He settled there writing many of his greatest works. A few years later in 1927, he became a British subject. Eliot passed away on January 4, 1965, in Kensington, London where he spent the remaining years of his life.

T.S. Eliot's "Four Quartets", in the original format, Burnt Norton, East Coker, The Dry Salvages and Little Gidding

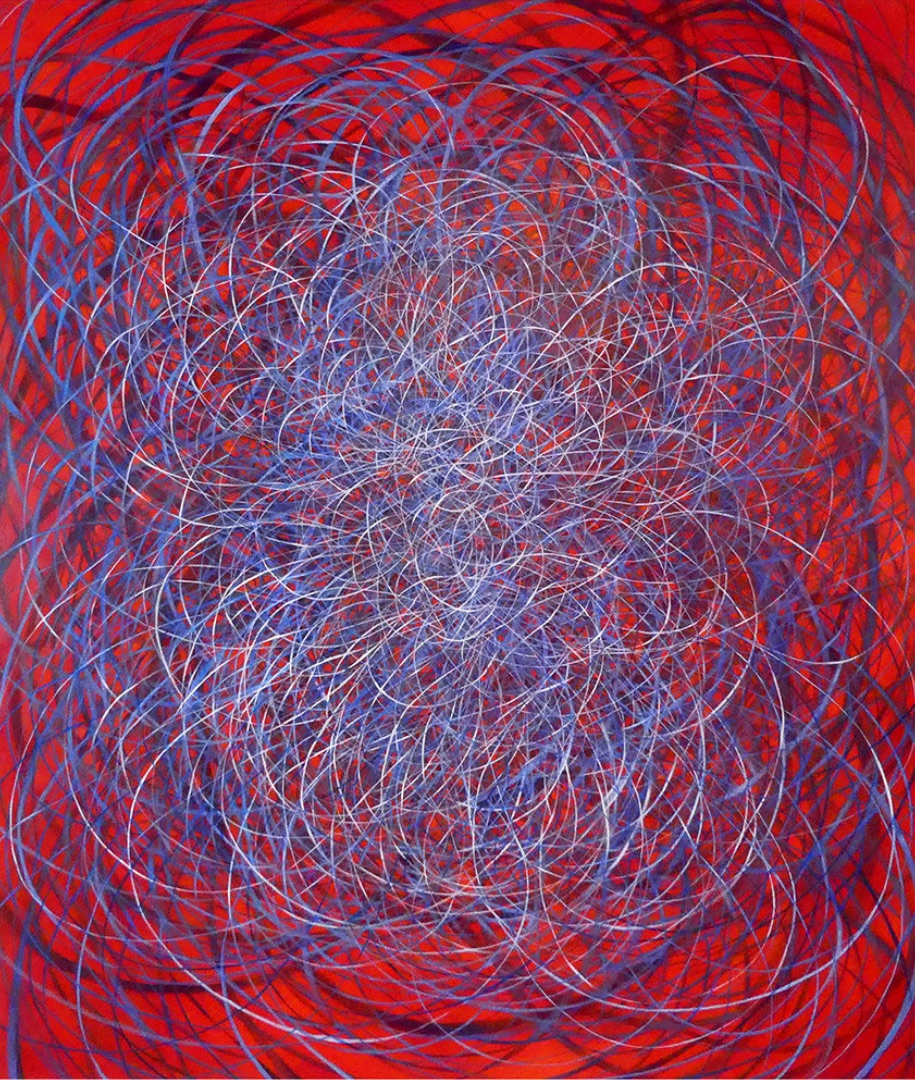

The line, Trilling Wire in the Blood may describe war, the blood of soldiers, and the fear of mass destruction. Interestingly, Guffogg made a painting after this stanza. His painting is quite compelling as the lines move to tell a story, narrating the pulsating heart, and the damnation of a country. Blue and white electric wires cover a field of cadmium red. The white scores within the blue and stand on end -- more blue lines fall into the background as tension and chaos fill the painting. Somehow in the midst of such commotion, the composition is contained like a twisting tornado seen off in the distance that is seemingly expanding as we look into it.

I asked Guffogg why he felt a need to create a painting with this title? I say need, because, like Rilke’s advice to the young poet, I believe Guffogg is an artist whose art form is likened to air – he can’t exist without it. I think he creates art to improve or commune with what already exists. This title is of a seemingly different cloth. What I have witnessed about him is that he is an artist that takes risks by going outside of his comfort zone. When I walk into his studio and look at a new painting, I see that he is deep within this artistic dialogue. Many things are in motion, evolving, and I am quiet as not to interrupt his creative flow. Later, I ask questions about his choices of titles. He replied with little hesitation.

At The Still Point Of The Turning World -

Trilling Wire in the Blood, 2017

oil on canvas, 80 x 70" inches

Shane Guffogg: Trilling Wire in the Blood and Appeasing Long Forgotten Wars, are titles that refer to the horrors of war. I have never lived in an actual war zone or been to war, but my father grew up in Northern England during WW2 and has very clear and frightening memories of the air sirens going off, announcing when Nazi warplanes were spotted heading their way and everyone had to get to safety. But I also look at these titles as something that is happening within each person. How often have I felt at war within myself over something or someone? Many times. How often did those emotions feel like a strange vibration that was coursing through my veins?”

At The Still Point Of The Turning World -

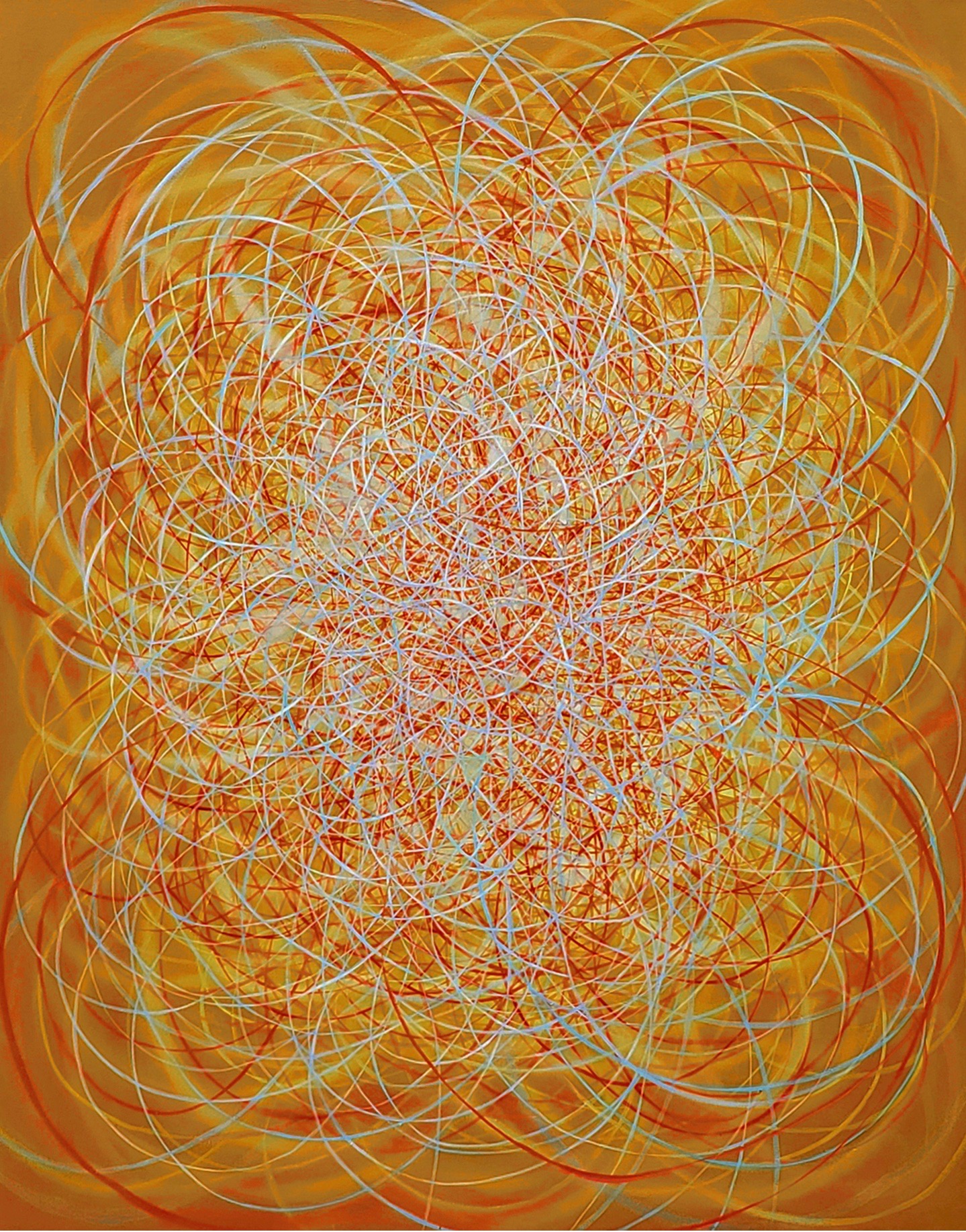

Appeasing Long Forgotten Wars, 2013-2016

oil on canvas, 60 x 48" inches

His comment about the inner war struck a chord with me. Guffogg has kept a journal from the beginning of his career, documenting how he has arrived at his current creative place. I read a section dated 1992 and thought it touched a similar chord on how his intuition guides him to create.

Shane Guffogg: “My new life on Western Ave was humming along in the fall of 1992. After spending some time setting up my new studio ... I was finding my rhythm, putting in a half a day's work on the building and a full day of painting, working late into the night. What began to emerge more and more from these midnight painting sessions was the human form. It wasn't because I was purposely trying to paint the figure – it was emerging from the Flight Pattern image of a radar screen I found in a magazine and was referencing as my means of making marks. I was now splicing and overlapping the markings. Patterns within patterns were being formed and they were almost recognizable, but as what, I wasn't sure. And to push the figurative envelope further, I started using fleshy reds. The dots for the flight patterns would often disappear under the layers of paint, so I started building them up with oil sticks, rubbing the paint into the drawn marks over and over. The oil stick paint would develop a skin overnight, allowing me to do a second and third layer quickly. Once the marks were between an eighth and quarter of an inch thick, I would begin painting the layers of deep red paint mixed with the glazing medium, Galkyd.

The oil stick markings seemed like an ancient counting system or information code of some sort, which got me thinking and looking at prehistoric cave paintings again. Thankfully, Arnold, the book dealer whose storage space was next to my studio, had a vast supply of material and was always willing to make me a deal. Arnold also had a series of medical books with lots of photos of muscles and tendons, bone and bone marrow, cells, diseased skin, etc. Taken out of context, these images were pure abstraction. But they were functioning in a similar way to the planes on the radar screen, as in, they were all interacting with everything around them. Not one shape or mark was independent of the others – they were all interconnected. And now that I had to commute across town to Venice when Ed [Ed Ruscha] needed me in the studio once a week, I was thinking about the freeways of LA and how interconnected they were to the city itself and all the cities within cities and within that are all the people, all moving about in their cars or walking along the sidewalks. The macro of the city was mirroring the micro of the human body. It was like an unspoken code which led me back to the abstract markings in cave paintings, which, by the way, nobody has yet figured out what they mean.

I was tapping into something deep and profound, or at least it felt that way. My studio was lined with canvases, all with these primitive markings lathered in hues of fleshy reds. The images I was creating were going deep into the psyche, tapping into a source. I was feeling it and began dreaming about these paintings. They were codes to another dimension.

I was also continuing to explore how the turpentine made paint behave, which led to a happy accident. I had been painting on a medium size canvas, and laid it down on the floor to spray turpentine on it so the pigment would become liquid and gravity would move the paint, leaving a trail of pigment. I started this process but something distracted me, a phone call would be my assumption. I didn't spray a lot of turpentine on the canvas so it didn't make the paint run, instead, it butted up to the edge of the fresh paint and started to eat away at the edges. When I noticed what was happening I grabbed a paper towel and soaked up the turpentine from around the edges to stop it from going any further. What it left was a patch of semi-transparent paint that looked like it was a torn piece of rice paper that had landed on the surface of the painting. It was a strange thing that I was looking at and I decided to play around with it on other paintings. I eventually got around to using a flesh color over the deep reds, creating a look of torn skin, which I saw as pushing the idea of figurative painting in a new direction, at least for me. By 1993 I was in full motion with small paintings like Voluspa, a Nordic word that refers to the beginning and end of the world, and Gyoll, which is the river that separates the living from the dead.”

Voluspa, 1993

acrylic and oil on canvas, 24 x 24" inches

Gyoll, 1994

oil on canvas, 12 x 12" inches

After reading these pages I came to an understanding that Guffogg wasn’t afraid to walk along the battlefield of Eliot’s poem - his inquiries are limitless and willing to slow-dive into the soul.

In continuing with Eliot’s poem, we move to lines 54-63

Dance along the artery

The circulation of the lymph

Are figured in the drift of stars

Ascend to summer in the tree

We move among the moving tree

In light upon the figured leaf

And hear upon the sodden floor

Below, the boarhound and the boar

Pursue their pattern as before

But reconciled among the stars.

There is a transition with the next stanza, Circulation of the lymph, the analysis I am reading suggests the writer is making a connection between the flow of our bodily fluids and the movement of the universe, which brings about a kind of spiritual manifestation. The coupling between our bodies and the stars is what allows us to ‘ascend’ from the previous talk of ‘mud’ to summer in the tree. Eliot continues on saying that humanity is stuck in the dying days of autumn – like a dead leaf in the mud of spiritual emptiness. But now he says our relationship with the stars, which allows our spirits to ascend, returning us to leaves and even (our souls) maybephysically and symbolically unfallen. How profound! I learn, from this new place of spiritual illumination, ‘up in the tree’ we can see the boar and boarhound chasing and killing each other. These actions don’t seem pointless from this new perspective since we know that the “pattern” is Reconciled among the stars. I think what Eliot is trying to say, is that everything has a cycle and through life or death, it is connected to the universe.

Just as Guffogg starts with one painted line, adding more, erasing some, revealing layer upon layer, there is a beginning, middle and end. I have been told that creation, including painting, has its own cycle of destruction. With every other movement of the brush, Guffogg creates a line and then takes one away. He covers the surface with paint and then removes a field of it, all the while working toward an outcome. This cycle goes on for months on a single painting, even sometimes years, depending on the relationship he has with the subject and the progress it brings. There is always a space of inquiry. Guffogg is following his own discourse, reaching for the truth within his own inherent provenance.

We begin another dialogue. I ask him questions about the obvious. What does At the Still Point mean to him?

Shane Guffogg: “The Still Point is an idea, or in my case, I could say it is a philosophy that points to a practice - a state of mind that leads to a way of life. And that, to me, is finding my center, which allows me to have balance in my life.”

CLICK HERE TO VIEW Shane Guffogg Studio Practice

I then ask about permanence and why is it so important to continue to paint and make it last for centuries?

Shane Guffogg: “Painting is one of the oldest forms of visual communication. The drawings that were made on cave walls around the world go back as far as 40,000 years. That is a very long time ago! They had the wherewithal to make their art deep inside caves, which means they were protected from the elements. We can only imagine how much art was lost over time that was exposed to weather. And imagine if the cave art was never found or preserved. What would we know about our ancient ancestors? Not much I am afraid. If we cannot learn from our past, and especially our distant past, how can we as a human race expect to progress forward? I am constantly reading that new discoveries in Egypt or South America are being found almost weekly and with each new discovery is new information that takes us back in time as we learn about how they lived. These discoveries give us something real to measure ourselves by.”

And what do we learn through all this?

Shane Guffogg: “How to be more humane!”

At The Still Point Of The Turning World -

So We Moved And They In A Formal Pattern, 2018

oil on canvas, 34 x 24" inches

At The Still Point Of The Turning World -

So We Moved And They In A Formal Pattern #2, 2018

oil on canvas, 34 x 24" inches

As I move back to Eliot and the next few lines, 64 – 69, these are the words that are Guffogg’s main inspiration for the entire series he started in 2009.

At the still point of the turning world,

Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is,

But neither arrest nor movement. And do not call it fixity,

Wherepast and future are gathered.

Neither movement from nor towards,

Neither ascent nor decline. Except for the point, the still point,

There would be no dance, and there is only the dance.

I find these stanzas are extraordinary. Every time I read it aloud, I feel I am informed about something beyond my understanding, and I am being led to a place of knowing. I wonder if Eliot is looking for a sense of permanence in a world of change? This includes the past, the present and the future – the writer knows we can’t change the world, but we can adjust our thoughts. The analysis says the term, At the Still Point of a Turning World is a good way to understand this and lines like, nor towards,speak of opposites. I think about my day to day life, and this is what I struggle with. Is the Still Point a place that is physical or is it spiritual? Then in the poem, Eliot references Dance. My guides wonder if Eliot was influenced by W.B. Yeats, and his poem, Among School Children, where he says, “How can we know the dancer from the dance?” This to me is uncovering many things that I have witnessed. One is Guffogg’s process of painting, which is similar to the art of Tai Chi. Guffogg uses his entire physicality to create each stroke, and in every moment, the very energy in his soul is beaming to make those strokes. He paints for hours upon hours every day of the week. Rarely does he take a break. Working alongside him, I would not say he is addicted to painting, it is something that summons him. The Still Point series began in 2009, but with this latest three- year evolution, the paintings have become larger not smaller, with plans to go even bigger, creating visual oceans to explore. Guffogg is finding his cue from somewhere or some place that is unknown to me -- he is following a light in the dark and moving towards its source. Day after day, he picks up his brush, moves, lingers, seeing, searching where to begin – it appears he is diving off into a place of nonexistence. According to Eliot, this is a place that is neither moving or still, we can’t call it fixity or stillness because we can’t stop the world around us from moving.

Instead, the analysis explains Eliot is referring to a place where movement happens for its own sake, in the now, that all of time points us toward; but there is only the dance.

Eliot’s next group of stanzas describe this further,

I can only say, there were have been: but I cannot say where.

And I cannot say, how long, for that is to place it in time.

The inner freedom from the practical desire,

The release from action and suffering, release from the inner

And the outer compulsion, yet surrounded

By a grace of sense, a white light still and moving

At The Still Point Of The Turning World -

A Grace of Sense, A White Light, Still And Moving, 2018

oil on canvas, 60 x 60" inches

This is stated beautifully, uncovering the sense of the place and that it is a stretch of a few words or comprehension.

Time past and time future

Allow but a little consciousness

To be conscious is not to be in time

But only in time can the moment in the rose garden,

The moment in the arbour where the rain beat,

The moment in the draughty church at smokefall

Be remembered, involved in past and future

Only through time is time conquered.

I had to ask Guffogg about this title, Allow But A Little Consciousness and his concept of his rose garden, whether it was spiritual or concrete, and his over-sized painting, Only Through Time Is Time Conquered. I wondered if he could share any developments in creating these works, what the process teaches him. From my experience working with others, an artist may set out to create a painting and those that do not paint, may merely see it as a task. But they are quick to explain, it isn’t that at all. It can be a tug of war, pulling at your heartstrings or desperately trying to divulge something that one is not ready to expose. Artists can struggle with their works and some may just land into the category of what Eliot was describing; a dance. And that one might not realize they are the dancer at all.

At The Still Point Of The Turning World -

Allow But A Little Consciousness, 2017

oil on canvas, 60 x 48" inches

At The Still Point Of The Turning World -

Into The Rose Garden, 2016

oil on canvas, 60 x 48" inches

Shane Guffogg: “I am naturally drawn towards using earth tones in my work. By taking lines from the poem of TS Eliot, it opens doors for me that I might not have thought to open. Having a set of words in front of me allows me to wander into his world. And believe it or not, having these predisposed parameters is very freeing because it puts me in a place that I can wanderwithout restraint. I associate colors with words or even sounds. For instance, when I think of consciousness, I think of light because to me, it references illumination. When I think of time, it has a weight to it that is indescribable, yet it is weightless. What colors would I choose to express this conundrum? Colors that are light and dark, coming forward and receding into the picture plane simultaneously. Eliot's words are a portal for me to step into and rethink my thoughts, rearranging my own patterns that manifest in the movement of my hand and brush strokes. On the surface, the paintings look similar, but when they are looked at side by side, one after another, there are changes that occur that is being conducted by my own thought process of how I am thinking about the meaning and essence of a word or phrase, especially within the context of the Eliot poem, which I think is a masterpiece.”

The art fairs that descended on LA added to the constant choir of noise, made ofsirens, helicopters and millions of people that permeate this city. I walk into Guffogg's studio on Monday after being away for a few days and he has again, tapped into another part of the poem that summons forth a moment that stops me and realigns my senses. The painting is exactly what the Doctor ordered; Reach into the Silence.

Shane Guffogg working in the large painting studio in Los Angeles on "Reach Into Silence"

A page from the artist's notebook, explaining which lines to make paintings out of and what colors may be appropriate

“The Still Point is an idea, or in my case, I could say it is a philosophy that points a practice - a state of mind that leads to a way of life. And that, to me, is finding my center, which allows me to have balance in my life." - Shane Guffogg

At The Still Point Of The Turning World -

Reach Into Silence, 2019

oil on canvas, 78 x 96" inches